What Counts as Pollution?

Counting Pollution

When there is something wrong with the fish, when you can see, smell or feel pollution, you know it is happening.

Pollution can last a long time. Persistent chemicals stay in the land and spread into animals, fish, and people across generations. Some of these chemicals come from a time before the Canadian government regulated pollution.

Yet many more harmful industrial chemicals continue to be put into the airs, waters, and lands because Canada is a permission-to-pollute government: it regulates pollution by allowing pollution to occur up to a certain amount.

More than this, the system of monitoring and regulating chemicals is purposefully built so as to minimize its effect to industry and the economy. Some of the world’s most powerful industry lobbies, such as from the oil industry, have worked hard to make sure environmental regulations do not interfere with their profits.

In 1975, the Canadian parliament passed the Environmental Contaminants Act, giving the government the authority to ban or restrict chemicals that pose a “significant danger” to the environment or health. This legislation put the burden of proving that chemicals cause “significant danger” on government ministries, rather than requiring companies to prove that the chemicals in their pollution and products are safe. Only one year after the act was put into effect, a federal government directive required that ministries do a cost-benefit assessment that weighed the economic impact of any regulation before it could be considered. 1

Thus only a very small number of chemicals have been banned. In 1977, Polychlorinated Biphenyls (usually known as PCBs) for which there was overwhelming evidence of their harm to humans and animals while also accumulating in lands and waters, was one of these chemicals. Despite being banned globally in the Stockholm convention in 2001, all people alive today on earth still have PCBs in their bodies.

Importantly, the science that helped to guide toxic substances standards also became part of the permission-to-pollute system. Industries that well knew they were involved in creating harmful exposures - from the tobacco Industry to the oil Industry, including ExxonMobil - became “Merchants of Doubts,” promoting ways of doing science and monitoring about pollutants that could create uncertainty about their effects. 2

Caught between weighing economic impacts in cost-benefit analyses, on the one hand, and the bad-faith promotion of scientific uncertainty, on the other, even well-intentioned government scientists have rarely been able to use research to create legally binding reductions to pollution.

Data not Control

Collecting data about pollution is the main form of environmental governance.

When Canada established the Ministry of Environment in 1985, environmental governance was strongly influenced by the participation of industry lobbying and the “cooperative” approach with industry. The Ministry’s activities focused less on making legally-binding curbs to pollution than on requiring the monitoring of pollution and "negotiating" the voluntary reduction of pollution.

In Canada, the province has the responsibility of regulating pollution directly. Environmental regulation in Ontario, is also based on this “cooperative” model, where the government negotiates with polluters around setting standards. Individual facilities and sectors can even negotiate their own tailor -made, site-specific standards well above provincial standards.

The Canadian government depends on industry self-reporting to know if standards are met or broken.

Following in the footsteps of the United States, Canada began asking industrial facilities to self-report on their pollution emissions in 1992. The National Pollution Release Inventory (NPRI) requireed facilities to report some 78 chemicals when their emission rates were above specific level (often in the tons). Today the NPRI reports on some 300 chemicals.

The NPRI, like most other monitoring systems, tends to report pollution one chemical at a time, year by year, and facility by facility. This makes it difficult to see the way chronic pollution adds up, as pollution tends to be made up of many chemicals, and in Chemical Valley, pollution is always chronic and complex.

At the same time, companies are not required to share their more detailed data about emissions and spills with the public, as their data is treated as the private property of the company, and even if the Ontario Ministry of Environment acquires such data, it is legally prevented from sharing it with the community and public.

Beyond the NPRI, information about a particular facility's pollution, like the Imperial Oil Refinery, is sparse.

When spills, leaks, or flares happen, companies in Chemical Valley often report what is released vaguely, using categories like “hydrocarbons” that can indicate any number of hundreds of chemicals. Or even if a specific chemical is named, such as in an air monitor, the information provided is just a technical name and numerical measure. What it means for the well-being of people or the community is not connected to the measure by a monitor.

The National Pollution Release Inventory

The National Pollution Release Inventory (NPRI) is both an important source of data and is profoundly inadequate. Because it is industry self-reported data, it reflects the companies conflict of interest in revealing the extent of its pollution responsibilities.

Why the NPRI is Useful

NPRI data is useful for one main reason. It is one of the few sources of data that attaches pollution to a specific facility. Every year, facilities are obliged to report on their emissions, leaks, and disposals of some 300 chemicals.

Chemicals only become part of NPRI reporting when there is a strong evidence that the substance is causing harm. So for each pollutant that is reported, there is a wealth of peer-reviewed scientific studies showing its harms.

Thus, the NPRI is one of the only admissions that companies make about their pollution activities.

This is why the NPRI is used by the Pollution Reporter App: the data is used to attach responsibility for pollution and health harms to specific polluters.

Industry Self-Reporting: Bias Is Baked In

The NPRI is also profoundly flawed.

The NPRI is based on industry self-reported data. So there is a built-in conflict of interest within this data.

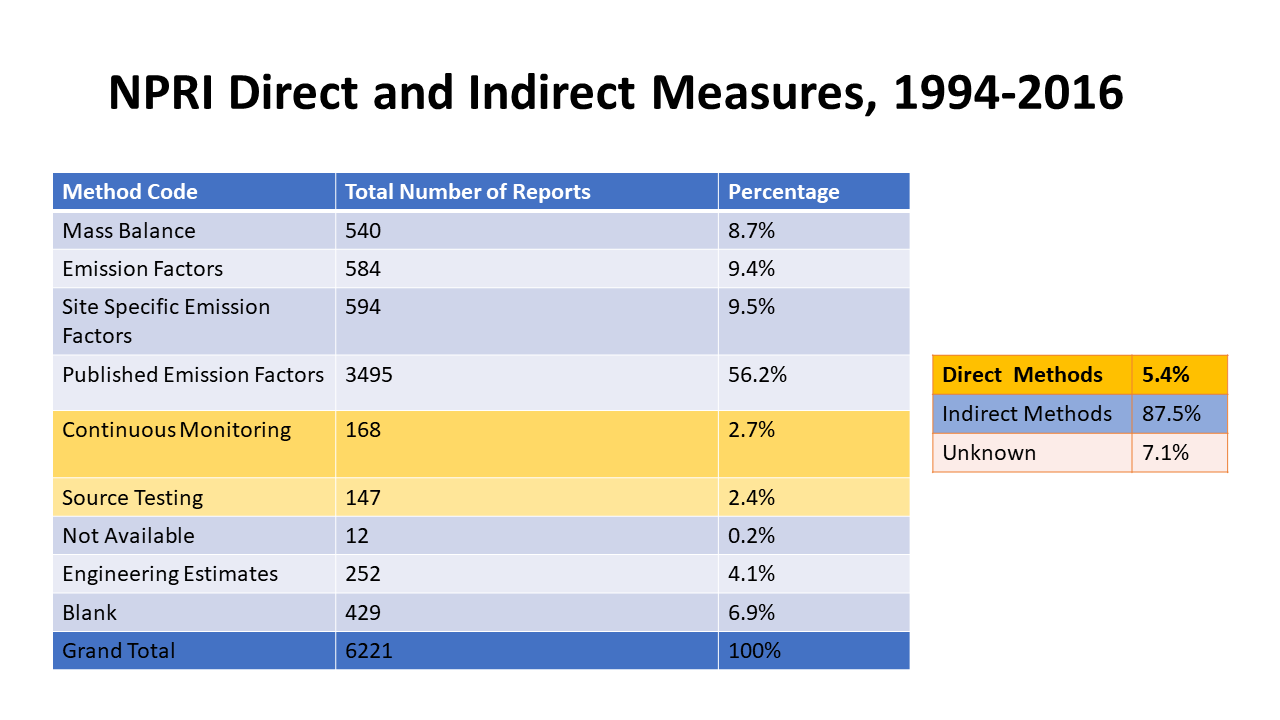

Moreover, there are multiple methods that the government allows companies use to report their data. Ideally, companies would have to take physical measures, and materially monitor their pollution activities as they happen. This is almost never the case.

One of the most popular methods for self-reporting pollution is called “indirect methods.” This means that companies can estimate their pollution levels using only calculations, and not based on any physical measure what so over. Calculations are based on numbers called “emission factors” which are estimates of the amount of emissions that a particular industrial activity creates based on either its material inputs or outputs (such as barrels of oil refined). These emission factors are created by non-government committees staffed with industry representatives, and thus tend to be conservative, under-estimating pollution levels in ways that benefit industry.

By using indirect measures based on mathematical estimates, we cannot see the difference in pollution levels between a refineries, such as between very old refineries, such as the Imperial Oil Refinery, and a brand new refinery, or between companies that may be more or less diligent when it comes to the care of their facilities.

The Auditor General of Canada investigated the quality of NPRI data in a 2009 report that concluded

“Environment Canada does not have adequate systems and practices in place to verify that all facilities required to report their emissions are doing so and that the information they report is accurate." (footnote 3)

Bias is baked into the NPRI numbers.

Chart of Direct and Indirect Measures in NPRI 1994-2016

87% of NPRI measures at the Imperial Oil Complex in Sarnia were Indirect Measures from 1994-2016

Notes

J. F. Castrilli, “Control of Toxic Chemicals in Canada: An Analysis of Law and Policy,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 20, no. 2 (1982): 322–401.

Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010)

Auditor General of Canada, “Report of the Commission of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the House of Commons” (Ottawa: Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2009)