Pollution is Colonialism

Permission to Pollute Systems

You can see the smoke coming out of the stacks, you can smell something like rotten eggs? or windex? in the air. You can see the large flares burning through the night.

The pollution shows itself in the health of plants, or in the well-being of the fish. The reality of pollution is obvious to the senses.

Yet the air monitor is inconclusive, or the corporate press release declares that no unsafe emissions occurred. The government fails to stop the pollution you can see and feel.

Canada and Ontario are permission to pollute governments. When these governments created environmental regulations about airs and waters beginning in the 1970s, those regulations always allowed pollution to continue up to a certain limit.

Not only was pollution allowed to continue, but the ways of monitoring pollution ended up hiding pollution as much or more as they demonstrated pollution.

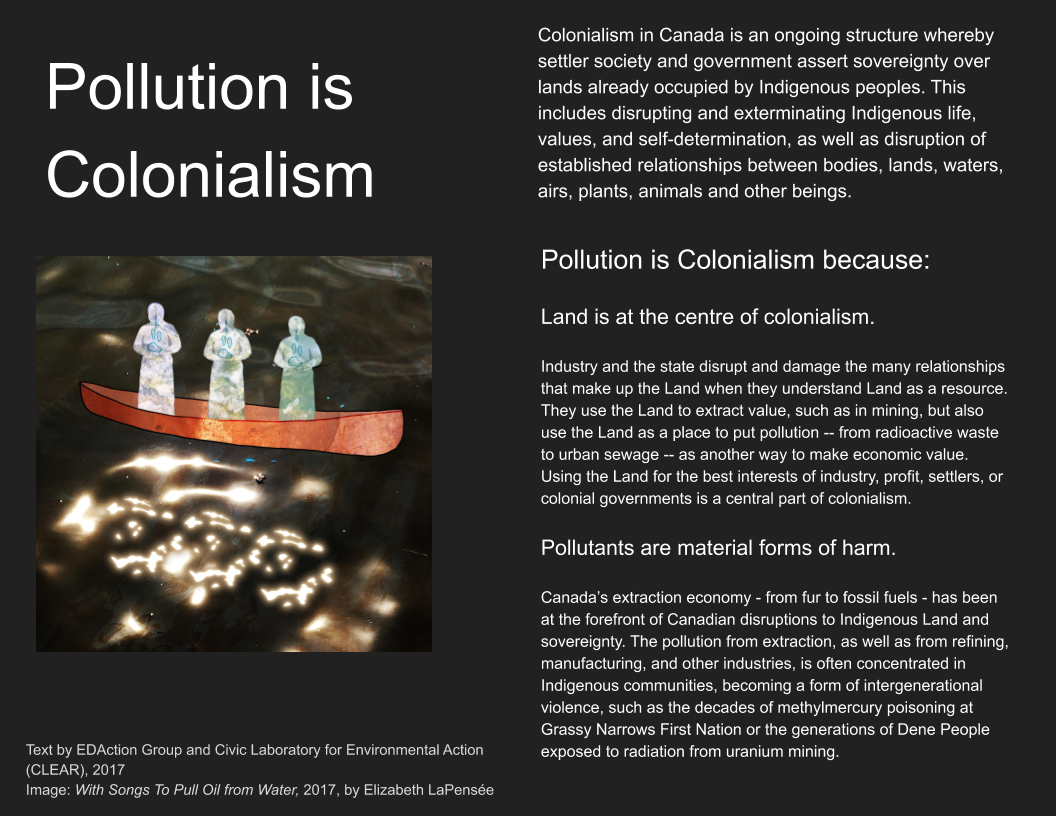

Pollution is Colonialism

Land is at the heart of colonialism in Canada. Pollution enacts colonialism physically when it disrupts land and life on Indigenous territories.

Smoke plumes and contaminants in waterways do not respect borders or treaties. Pollution does not respect obligations to non-interference in land and Indigenous life, and disrupts the well-being and relationships of animals, fish, birds, and plants.

In Canada, the concentration of pollution near Indigenous communities is linked to the legal fiction of “terra nullius” or empty lands. Settler colonialism was able to claim land by saying its was empty or being “wasted” because it was not being put to proper productive use, despite the presence of Indigenous and other-than human communities. “Wastelanding” names the ongoing process of treating the lands inhabited by Indigenous, Black and poor communities as empty and therefore in able to be sites for further wasting by concentrating intensive pollution.1

One provocative way of defining racism is as the disproportionate exposure to early-death, with pollution adding to the chronic and concentrated dangers that threaten Indigenous people.2

All along the Great Lakes, pollution is concentrated in places of intensive industry and extraction, whether with mining, oil extraction, petrochemical refining, manufacture, or paper and pulp mills. Exposures to pollution are concentrated in Indigenous communities, poor communities, or Black communities all along the St Clair and Detroit Rivers. The concept of environmental racism was developed by African-American land protectors in the 1980s who showed that landfills and waste sites were overwhelmingly concentrated near black communities.3

Indigenous Land protectors have shown how "Violence on the Land Is Violence on our Bodies."

Pollution is also a form of colonialism through the Canadian state’s permission-to-pollute governance system. Designed to allow industries to pollute up to a particular level, Canadian and US environmental law on both sides of the St Clair River allow ongoing disruption to Indigenous territories, but also refuses to acknowledge Indigenous sovereignty or the nation-to-nation relationship by claiming the right to govern pollution as its belonging to colonial state. Leaks, spills, and accidents, as well as chronic pollution, are considered acceptable risks. The Canadian and US states both claim the right to decide the terms and rules by which what kinds of exposure to pollution take place.

Lastly, pollution is colonialism because it is made possible by the way the Canadian and US governments, along with corporations, treat the land as “natural resources” as things that can and should be be bought and sold, and to which anything can be done, including destroying, when owned.

Our understanding of pollution is colonialism is informed by generations of Indigenous land protectors at Aamjiwnaang and around the Great Lakes, the work of Métis scientist Max Liboiron at their lab CLEAR, and the Pollution is Colonialism framework developed CLEAR and EDAction.

Pollution is Colonialism pamphlet by EDActio and CLEAR

Notes

Traci Brynne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

United Church of Christ Commission on Racial Justice: A National Report on the Racial and Socio-Economic, “Toxic Waste and Race in the United States: Characteristics of Communities with Hazardous Waste Sites,” 1987.

Glossary

rotten eggs -- The smell of rotten eggs indicates the presence of a substance with sulphur, such as the gas hydrogen sulfide.

windex -- The smell of windex in the air indicates amonia.