One Well to Four Hundred Wells

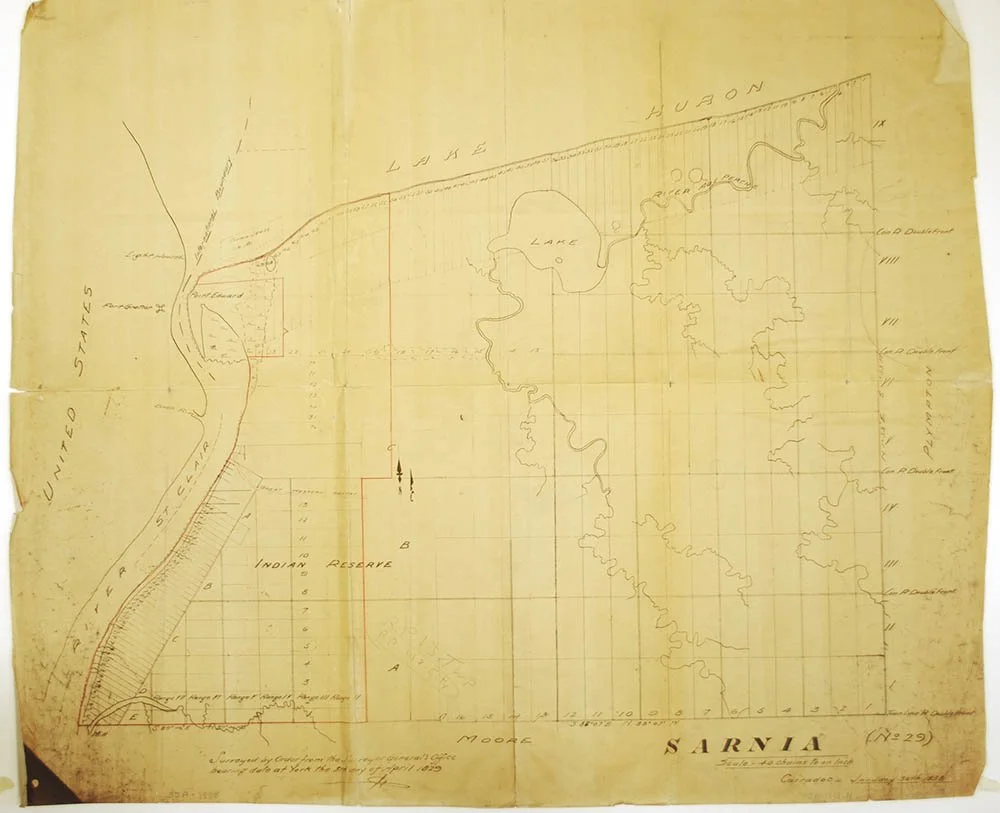

The 1829 survey that shows the boundaries of the Sarnia Reserve after the 1827 Huron Tract Purchase. The survey divides the Land into parcels that can be used to facilitate future land sale.

How did the gum beds become an oil field?

How did one well turn into four hundred wells and “Canada’s Oil Lands?”

When Canada was still the Province of Canada and one of the territories of the British Empire in North America, there were no restrictions on what settlers could do to the Land. There were no laws against pollution or protections for the Land. As a resource, Land was something to drill into and extract from, not something to be in good relation to.

The Huron Tract Purchase

In 1827, the Huron Tract Purchase, or Treaty 29, established four small reserves, one of which covered the 10,280 acres where Aamjiwnaang First Nation is now located along the Gichigami-ziibi (Sea River) or St. Clair River. Whenever reserves are established, Land is ceded or “surrendered,” but First Nations continue to contest whether treaty lands include a ceding of subsurface rights. (footnote 1) In this case, part of these ceded lands became the first oil field, in what is now named Oil Springs. The forested wetlands and its “resources” were well known to the Anishnaabe people: oil welled to the surface in “gum beds” or “oil springs” and Indigenous people used the oil with respect treating it as a gift or a relative, not a resource.

In 1854, the Tripp brothers arrived to this sacred land with a charter from the Province of Canada to establish the world’s first oil company with the aim of turning oil from the gum beds into asphalt for roads or sealant for water-crafts. Their empire-building visions are confirmed in the company’s title: The International Mining and Manufacturing Company. (footnote 2)

Read the Charter of the International Mining and Manufacturing Company Here.

Photo of Shaw's Well, Oil Museum, Lambton County Library

Shaw's Well

Their first oil well was hand dug and it took just fourteen feet for them to strike oil. It was 1858. Simple oil refining, using kettles, soon followed. In 1862, land speculators, people who purchase land in hopes that it will go up in value, found the first oil gusher, Shaw’s Well, which sprayed higher than the nearby trees at an estimated volume of 3000 barrels a day. (footnote 3) More oil was spilled than barrelled. (footnote 4)

Crude oil streamed into the Lands and creeks nearest the well. It spilled for ten months. Trees were shorn of their limbs, became twisted, and covered in crude black. (footnote 5) The air carried a thick stench. The high sulphur and arsenic sour crude oil of the area smell like rotten eggs. The oil flowed through the creeks, into the St. Clair River, through the mouth of the river and around Bkejwanong (Walpole Island First Nation) lands, and then into Lake St. Clair, which was then covered by a film of oil. (footnote 6)

What did settlers learn from this ten-month spill? As more wells were drilled into Oil Springs or Petrolia, prospectors took a habit of digging near creeks for easier diversion of spilled oil. (footnote 7)

The oil attracted more prospectors, small-scale “mineral explorers,” and land speculators. What happened next has been called an “economic boom.”(footnote 8) Plank roads were built. Some of these led to a bank. Others to the new railroad and pump stations. Pipelines were dug connecting to the first refineries.

This enduring infrastructure shows us that Canada has a long history of legalizing environmental violence. Before oil fields in Alberta, this area was called Canada’s first "Oil Lands.” Much like Fort McMurray today, this Land of wells saw a rush of male settlers arriving to build and support this infrastructure. Their arrival put more pressure on the Land and land acquisition from settlers. By August of 1861, some 400 wells had been drilled in the area. (footnote 9) More refineries followed, many of which were slapdash operations boiling oil in simple kettles for quick profit.

Notes

Telford, Rhonda Mae. 1996. “The sound of the rustling of the gold is under my feet where I stand, we have a rich country, a history of aboriginal mineral resources in Ontario.” PhD Dissertation. University of Toronto: National Library of Canada.

Burr, Christina Ann. 2006. Canada’s Victorian Oil Town. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Ewing, John. 1951. “The History of Imperial Oil Limited.” Vol 1. Harvard Business School: Business History Foundation. IOLpub-1a-5. Glenbow Archives, 49.

Ewing 1951, 48.

Ewing, 1951, 30.

Ewing, 1951, 49.

Ewing, 1951, 55.

Burr, Canada's Victorian Oil Town. For an celebratory account of oil prospecting history in this area see also Gary May, Hard Oiler!: The Story of Early Canadians’ Quest for Oil at Home and Abroad (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1998).

Burr, Canada's Victorian Oil Town, 47.