Industry Self-Reporting

Self-Reported Data at the Imperial Oil Refinery

The Imperial Oil Refinery in Sarnia is required like all other refineries to report its pollution releases once a year to the Canadian Government through the National Pollution Release Inventory (NPRI).

The NPRI was developed using a "consultative model" in dialogue with industry "stakeholders. (footnote 1) Industries lobbied hard to define exactly how they would have to report their pollution.

As a result, the information Imperial Oil provides to the NPRI are overwhelmingly not based on physical measurements taken at the refinery, but what is called "indirect measures." Indirect measures use mathematical estimates to report pollution, and the same method of estimation is allowed to be used at the oldest operating refinery as a brand new refinery.

So what do the numbers Imperial Oil provides actually tell us?

They may tell us more about the permission-to-pollute system of regulation than the pollution itself.

Imperial Oil and the NPRI

Archival papers at the Glenbow Archive give us a glimpse into how Imperial Oil approached the question of pollution monitoring.

When engineers and refinery managers at Sarnia’s Imperial Oil Refinery found out that the Canadian government was planning to make pollution reporting mandatory, they began to research the methods they could use.

The task was daunting because the refinery collected almost no information about its emissions.

The United States had already implemented similar legislation, called the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) in 1986 as a community-right-to-know legislation, in part inspired by the refusal of Union Carbide to release information about the gas and chemicals involved in the Bhopal Gas Disaster that killed thousands in 1985. Refineries in the United States had already been forced to implement a reporting system.

A team from Imperial Oil met with managers from other ExxonMobil refineries in Houston and Baton Rouge. These refinery managers warned the Imperial Oil Sarnia staff that once they started looking, they would be surprised by the emissions they found. “Every year [we are] finding ‘big ones’ we missed.” 1

As the NPRI team in Sarnia began to put together a plan for measuring releases, orders came from ExxonMobil’s management that they should stop their local work. ExxonMobil had its own monitoring system that they wanted Imperial Oil to use.

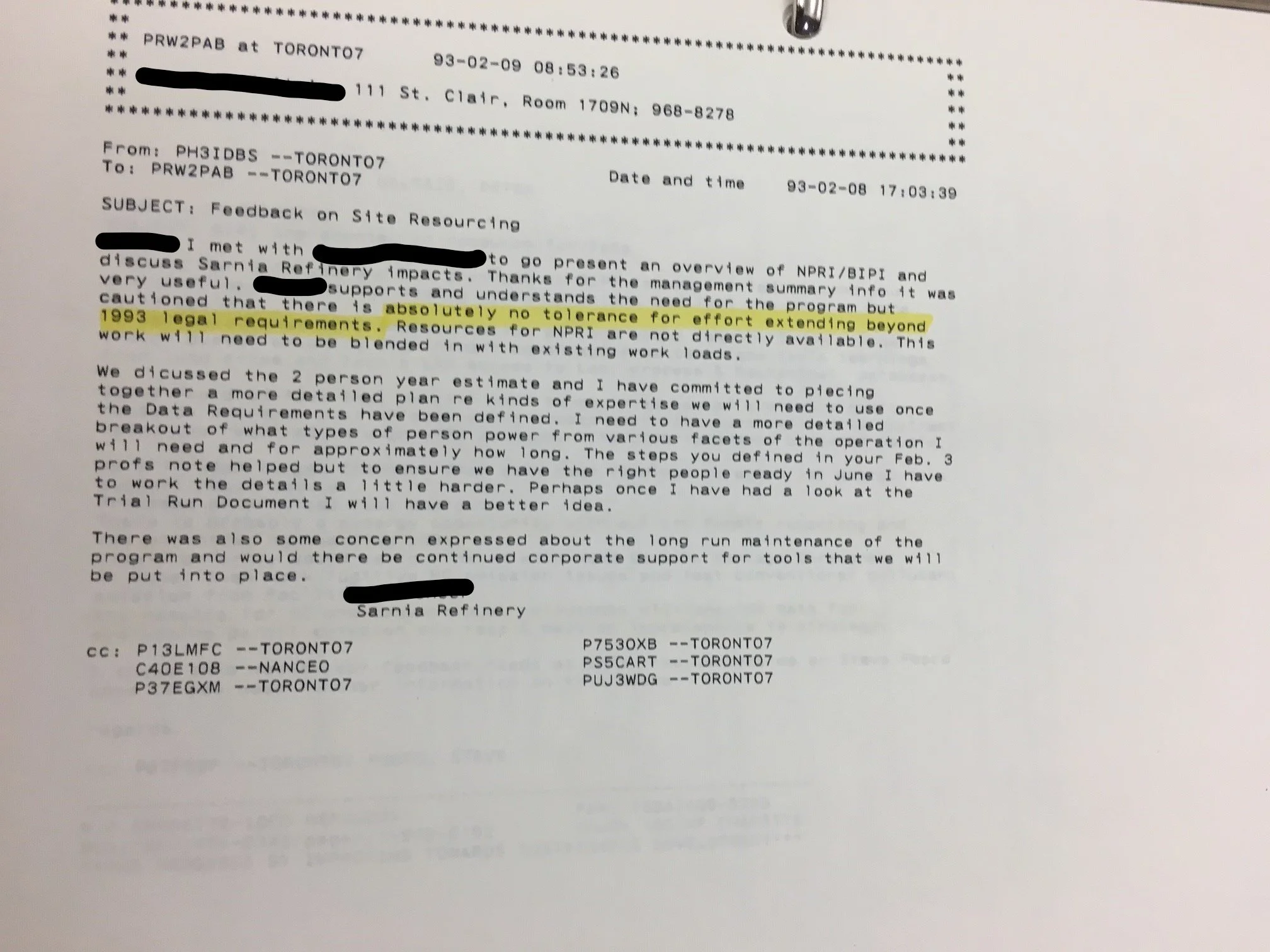

One key memo forbade engineers from taking any measure of pollution not required by law:

“There is absolutely no tolerance for effort extending beyond the 1993 legal requirements.” 2

Staff at the refinery were only to do the minimum required. Moreover, they were not to spend any funds on creating the monitoring data:

“Resources for the NPRI are not directly available. This work will need to be blended in with existing workloads." 3

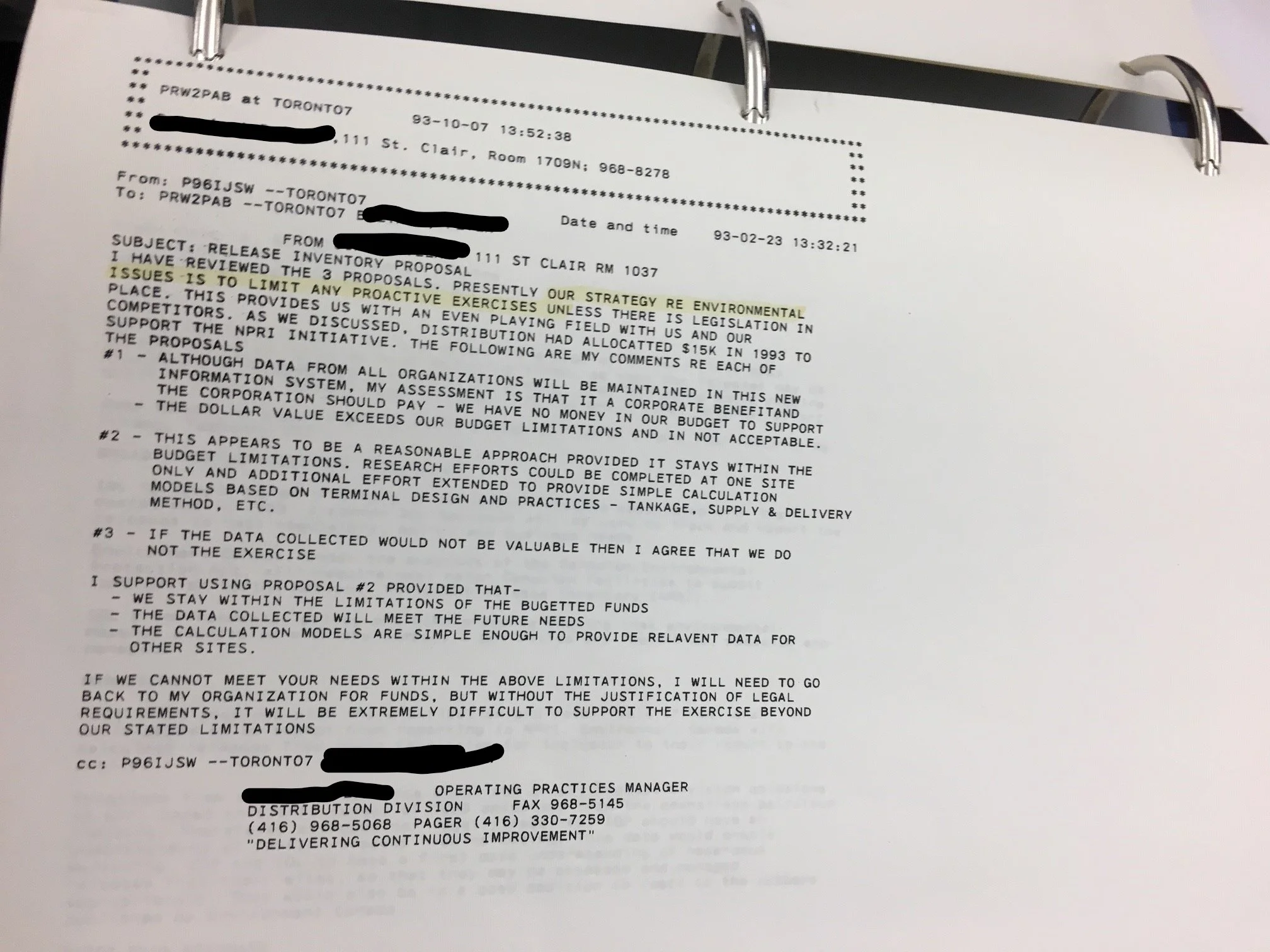

Another memo from the same period read,

“OUR STRATEGY RE ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IS TO LIMIT ANY PROACTIVE EXERCISES UNLESS THERE IS LEGISLATION IN PLACE” 4

From the very inception of the NPRI, ExxonMobil and other companies pushed for the acceptance of statistical estimates, over physical measures, for the NPRI. The management's ambition was to only take minimal physical measures to establish a baseline during the initial set up of the NPRI, and to use a software system to statistically generate estimates thereafter.

Internal documents from planning process outlined that Imperial Oil’s Sarnia Refinery to “represent conservative estimates of pollution releases,” and that they intended to “rely on defensible estimate with no or bare-minimum measurements.” 5

NPRI data shows Imperial Oil Refinery Biggest Polluter in Chemical Valley

Even after all this effort by ExxonMobil and Imperial Oil's management to set up a reporting system that did not require accurate physical measurements of pollution, the NPRI data provided is still damning.

According to the 2016 NPRI data, the Imperial Oil Refinery reported a total of 13,164 tons of emissions. This does not even include the emissions of the full Imperial Oil complex in Sarnia, that consists of its chemical plant, its power plant, and its transportation and storage works.

The next biggest polluter in Chemical Valley is Cabot Canada, which reported 7,262 tons. That is 45% less emissions than the Imperial Oil Refinery..

Imperial Oil bought the refinery operations in Sarnia in 1898, and the refinery itself goes back to 1871, while NPRI emissions reporting only starts in 1994.

Cumulatively Imperial Oil is responsible for some of the largest and most long-standing emissions in Canada.

Notes

Handwritten notes by Sarnia Refinery staff person on meeting with refinery managers from Houston and Baton Rouge. Glenbow Archive, Imperial Oil Papers, IOL pub -3e-37a.

Email about management directive to Imperial Oil Refinery Sarnia NPRI Development Team, Feb 08, 1993. Glenbow Archives, Imperial Oil Papers, IOL pub -3e-37b. Anonymized.

Email from Toronto Operating Practices Manager to Imperial Oil Refinery Sarnia NPRI Development Team, Feb 08, 1993. Glenbow Archives, Imperial Oil Papers, IOL pub -3e-37b. Anonymized.

Email from Toronto Operating Practices Manager to Imperial Oil Refinery Sarnia NPRI Development Team, Feb 23, 1993. Glenbow Archives, Imperial Oil Papers, IOL pub -3e-37b. Anonymized. Footnote placeholder

Page from Sarnia PRI Implementation Draft Plan, April 27, 1993. Glenbow Archives, Imperial Oil Papers, IOL pub -3e-37b.